Gaming in 1998

The 1990s were a whirlwind decade for video games, with an incredible amount of change happening from the start of the decade to the end. For a snapshot of just how much the landscape of video games changed in the 90s take a look at November 1990’s release of Super Mario World on the Super Nintendo Entertainment system and then take a look at the December 1999 release of Shenmue on the Sega Dreamcast-- video game technology had evolved from 16 bit 2D pixel art to 128 bit 3D immersive worlds. The Super Nintendo and Mega Drive may have been cutting edge technology in the console world in 1990, but the 8-bit systems like Sega’s Master System and the Nintendo Entertainment System were still the mainstays of the year for most punters. Considering this, you could argue that the 1990s saw four generations of consoles in the span of ten years. This is even without mentioning the leaps and bounds that computers advanced in the same timeframe, and what would become the widespread adoption of the PC format.

Gaming technology made incredible advancements between 1990 and 2000.

In the early 90s the console hardware race was very much dominated by Nintendo and Sega with Sega’s Mega Drive/Genesis console (launched in 1988 in Japan) and Nintendo’s Nintendo Entertainment System (NES)/Famicom (launched in 1983 in Japan) and their Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES)/Super Famicom (launched in 1990 in Japan). Outside of the two major players, other manufacturers would try to enter the growing market.

Japanese corporation NEC would team with video game company Hudson Soft and release the TurboGrafx-16/PC Engine; the console was ahead of its time with 16-bit graphics in 1987, and even CD-ROM format functionality sold separately. Electronics company Philips would release the CD-i format in 1990. This hardware was co-developed with Sony, being a collaboration of two of the biggest electronic companies in the world. Initially intended to be a multi-use multi-media format to serve a wide range of uses from training, education and even point of sale at retail, it would become recognised by many as a games console. Arcade stalwarts SNK would also enter the home console market with their NeoGeo Advanced Entertainment System (AES). SNK took a different tact, and the AES was essentially a consolised version of their arcade hardware, the NeoGeo Multi Video System (MVS). As such it was an extremely expensive piece of home hardware (as were most of the games). Initially intended to be rented from shops, with no retail version for sale. Eventually demand became high enough that SNK released it to consumers with the console retailing for USD $649.99 in 1991! That would be over $1,400 in 2023!

The NeoGeo AES was comparatively hugely powerful, but also prohibitively expensive.

By the end of the 90s, Sega and Nintendo would still be in the top 3 for hardware manufacturers, but they would be a very distant second place to a newcomer. Having dabbled in the video game industry in the earlier parts of the nineties, Sony thundered onto the scene with their PlayStation console in 1994 and trounced both Nintendo’s Nintendo 64 and Sega’s Sega Saturn in terms of worldwide sales. The ‘arms race’ would continue into the late nineties with Sega releasing their Dreamcast in 1998 (which would ultimately be their last console) and Sony and Nintendo hard at work with their own successors.

The advancements in technology through this decade is staggering. Most gamers would have been playing with 8-bit consoles at the start of the 90s, and almost every game was relegated to a 2D plane. Where CD started as something of a novelty, it was the standard format for games by 1999, with only Nintendo using cartridges for their Nintendo 64. Through the years the norm moved to 16-bit, to 32 and 64-bit consoles and even to Sega’s 128-bit Dreamcast powerhouse. 2D pixels gave way to 3D polygons with increasing levels of detail and special effects. Even online play had gone from an obscure curio in early 90s consoles to the Dreamcast coming with a modem as standard and many games being designed around online play.

Moving away from the home, arcades themselves had gone through some wild ups and downs in the decade. Having suffered something of a decline in the late 80s with the growing popularity of home consoles, arcades experienced a renaissance in 1992 with the release of the Capcom’s seminal Street Fighter II. It would be followed by a fighting-game lead boom with titles such as Midway Game’s Mortal Kombat (1992) and Sega’s 3D fighting game Virtua Fighter (1993). Arcades would remain the place where players could experience the most cutting edge technology in video games, only beginning to be equalled by PC and consoles by the very end of the decade. Even so, arcades would provide immersive and entertaining experiences with sit-down cabinets for racing games, light-gun shooters and more. In 1998 arcades were still seeing many major releases, especially in Japan where arcades were much more popular than in the West. Many of these arcade hits would eventually make their way to home consoles and be some of the best loved games, as players craved to ‘bring the arcade experience home’.

Daytona USA’s 8 player cabinet is an example of an experience only available in arcades. Sega’s hugely popular racer would also become a sought-after home release. (Image from Flipper Arcade via https://twitter.com/mikko/status/1081586309473415169)

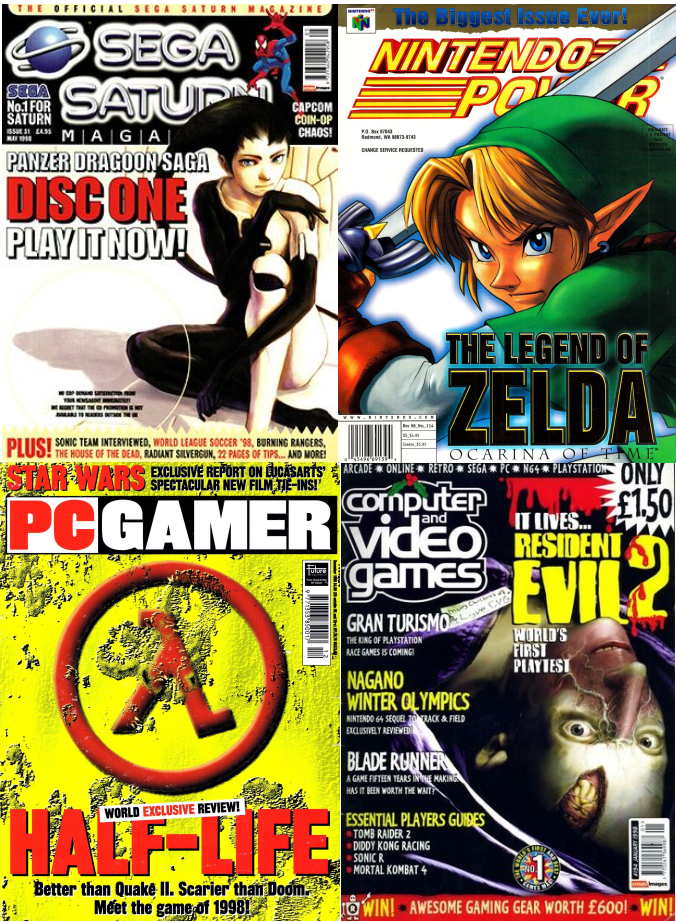

Gamers still primarily would get their news once a month via their favourite magazines, rather than getting a constant stream of information via the internet. A mix of official and unofficial magazines filled the newsagent shelves, with write-ups and screenshots of the latest games that were out now or coming soon. There were multiple magazines not only covering video games overall, but even multiple magazines for the same format. Players were spoilt for choice, and it wasn’t uncommon to pick up at least two magazines a month to get the fix of gaming news. Magazines often had a very irreverent tone and aesthetic, especially at the beginning of the 90s. The feeling of anticipation and excitement for new games was palpable when players would be drip-fed information, and reliance on imagination was a big part of the hype around new games. Having said that, sometimes gamers would get lucky and a magazine would have a cover-mounted CD (or in some rare cases, a VHS!) that had trailers for upcoming games, or even playable demos!

The Electronic Entertainment Expo was still very new (having been started in 1995), but by 1998 had grown to be the premier video game event in the world. It already had some legendary moments, with E3 being where many publishers would showcase their new games, and console hardware would be on display for the press to try for the first time ever. 1995 saw the ‘surprise’ launch of the Sega Saturn in the USA, and Sony’s aggressive move of undercutting Sega’s retail price by selling their PlayStation for $100 cheaper. 1996’s E3 saw the launch of the Nintendo 64 and subsequent price cutting by both Sega and Sony to counter it. By 1997, there were so many games being shown on the floor, of such high quality that magazines would struggle to cover it all in just one issue.

Computer & Video Games #190 struggled to cover E3 1997, even with 21 dedicated pages!

Video games were amongst the most popular they had ever been by 1998, and there was a perfect storm for video game development. Video games were ‘cool’, in part thanks to Sega’s Mega Drive/Genesis campaigns (such as ‘Welcome to the next level’) and the wild popularity of Sega’s mascot Sonic the Hedgehog. Nintendo’s ‘Play it Loud’ campaign changed the ‘child friendly’ look of Nintendo, and Sony’s huge marketing push to target the teen and young adult demographic with the PlayStation.

The market was big enough that it could support a huge amount of releases, but production costs hadn’t grown so large that publishers were too afraid to take risks on new ideas. By 1998, game developers had become very proficient with the hardware of the consoles, and were taking full advantage of what they could do. This extended to PC games too, benefitting from advancements with Microsoft Windows and the growing use of ‘3D Accelerator' cards. The result was games that looked better than anything we’d seen before. It was something of a nexus where small, creative teams of developers were able to realise their ideas and have them backed by big publishers and supported by a growing audience. Even niche games were able to become a success and find their audience on the store shelves. It was an exciting time to be a gamer, with just about every genre being represented, and a mix of old favourites being refined and brand new ideas taking form. Perhaps this mix will never be seen again, and it’s a big part of what made 1998 such a special year for games.